Introduction

In most of the other DGI Lessons, we’ve talked about reasons to buy a stock:

- Matching up companies with your investment goals

- Company quality and business model

- Dividend record and outlook, including yield, growth, and safety

- Valuation

For many investors, buying is the easy part. Knowing when – and whether – to sell is harder.

Once you have a portfolio established, how do you decide whether to hold or sell (trim) a particular position?

When buying, you are taking action. Buying is a proactive step, and it is human nature to take action. That is what most of us are wired to do.

Some investors have great difficulty keeping their hands off their portfolios, wanting constantly to tinker with them.

But messing around with your portfolio is often the wrong thing to do.

Studies have shown that most investors underperform the very securities that they invest in. How is this possible?

Because they trade too much.

The field of behavioral finance has demonstrated that many investors trade at the wrong times. They sell, emotionally, when prices are falling. By selling, they often lock in a loss.

Having sold, they wait too long to buy back in (because they fear the market), and thus they miss some gains that the actual securities make. When they finally decide to get back in, they are too late. They may pay a higher price to get back in than the price at which they sold.

Thus they underperform the security that they invested in. They would have been better off leaving it alone. Their emotional reaction to price changes ends up costing them money.

Dividend Growth Investing Can Help Behaviorally

Dividend growth investing turns your attention from prices to cashflow. It is a collection strategy where you benefit from buying and then holding onto what you already own.

Unlike other styles of investing, dividend growth investing is not about buying low and selling high. You are not trying to make money by flipping the stocks. Instead, you are trying to make money by collecting an ever-rising stream of cash dividends.

- First you collect shares of stock in excellent companies by buying them.

- Then you collect ever-rising streams of dividends from the companies that you own.

- Then you reinvest those dividends to collect more shares of stock.

- And then you collect dividends from them too.

Dividend growth investing is like being a landlord. A landlord buys properties so that he can rent them out. He makes money by collecting rents. He doesn’t flip the properties.

Dividend growth investing is similar. You are not buying stocks with the intent of selling them for a profit. You want the stream of dividends.

Don’t get me wrong. As life events happen, you will sell some of your stocks. But that is not your intent when you buy them.

In the rest of this lesson, we will presume that you have already built a portfolio of great companies. You are collecting the dividends and reinvesting them (or spending them).

Why might you consider trimming or selling any holding? That’s what we will explore in the remainder of this article.

Treat Selling in Your Business Plan

You have a business plan, right? We talked about running your investing like a business in Lesson 12 and constructing your business plan in Lesson 13. In my opinion, every serious investor should have a business plan.

Your business plan should contain guidelines for when you will consider selling a dividend growth stock.

Why? Because we always strive to make our investing activities rational. We don’t want to sell in a panic, churn our accounts, or over-trade. That is self-defeating behavior.

So as we talk about reasons to consider selling in the remainder of this article, think about incorporating the concepts that make sense to you into your own business plan.

Reasons to Consider Selling

Remember our basic business model: As a dividend growth investor, the goal is to collect, over time, stocks that pay a rising stream of dividends. The end-game is to live off those dividends in retirement.

Most of the time, that business goal is best served by buying, holding, and collecting stocks, not by selling them. Your account transactions do not include many sales. Most of the account activity is to collect dividends, add money, and buy more shares.

Here’s 3 recent months of activity in my Dividend Growth Portfolio:

All the transactions are dividends coming in, plus one purchase (marked by the red dot). There are no sales.

All the transactions are dividends coming in, plus one purchase (marked by the red dot). There are no sales.

But there will be times when selling or trimming a stock advances your business model better than just continuing to hold it.

Here are a few suggestions for situations when you might consider selling.

1. A stock cuts, freezes, or suspends its dividend

The logic here is obvious. Your goal is to own stocks that give you a reliably increasing stream of dividends. If one of your stocks cuts its dividend, it is not a “dividend growth stock” any more.

Famous recent examples of such stocks include:

- The many banks that cut their dividends in the financial crisis of 2008-2009.

- General Electric (GE), a former reliable dividend-growth stalwart that cut its dividend in 2009 and again in 2017.

- Kinder Morgan (KMI), a pipeline company that was long a darling of dividend growth investors, but which got caught in the oil squeeze and cut its dividend 75% in 2015.

I held both GE and KMI in my Dividend Growth Portfolio when they cut their dividends. I didn’t see the cuts coming, and in each case the dividend cut was accompanied by steep price drops. In the graph below, the 2009 GE experience is circled in blue, and the 2015 KMI experience is circled in red.

Unfortunately, in both cases major price damage had already occurred by the time of the dividend cuts. Selling locked in losses in both cases.

Unfortunately, in both cases major price damage had already occurred by the time of the dividend cuts. Selling locked in losses in both cases.

But I sold out of my positions, and the sales were not made in fear of further loss. The reason to sell in each case was the dividend cut. The reduced dividends for GE and KMI were inconsistent with my goal, which is to have increasing dividends.

As I look back on those decisions to sell, they were the right thing to do. Neither company has recovered either in share price or dividend payout. I deployed the money from the sales into other (better) companies, and the dividend cuts have been made up by the growing income streams from other companies in my diversified portfolio.

2. A stock bubbles or becomes seriously overvalued

I discussed how I value stocks in Lesson 11. In my Dividend Growth Stock of the Month articles, I summarize valuation in a table like this.

But what if the valuation summary looked like this?

But what if the valuation summary looked like this?

You might want to consider selling or trimming – especially if:

You might want to consider selling or trimming – especially if:

- You have an alternative company to invest in that is of equal quality, fairly valued, and paying a larger yield.

- The position you are considering trimming is excessively large.

You could increase your income flow instantly by making the swap. And increasing your income flow aligns with your goals.

Selling on the basis of severe overvaluation is something that I do seldom, but I have done it. One way to look at it is that by selling (or trimming), you may collect in profits the equivalent of several years’ worth of dividends.

If you can turn around and invest that money into a good company at a better valuation with a much better yield, it’s something to seriously consider doing.

Here is an example of making such a swap in my Dividend Growth Portfolio. In 2017, McDonald’s (MCD) had grown to occupy >12% of the portfolio. This happened because MCD had been on an upward price tear for 2 years.

One result of that price tear was that the stock became seriously overvalued. As shown on the next chart, McDonald’s valuation had levitated beyond historical norms for both the market (orange line) and McDonald’s itself (blue line).

Because yield and price are inversely related (see DGI Lesson 6: Yield and Yield on Cost), MCD’s yield had fallen to 2.2%.

Because yield and price are inversely related (see DGI Lesson 6: Yield and Yield on Cost), MCD’s yield had fallen to 2.2%.

So I had a situation where the McDonald’s position was overvalued, oversized, and yielding a low percentage.

So I had a situation where the McDonald’s position was overvalued, oversized, and yielding a low percentage.

So I decided to trim the position and put the money to work elsewhere. Here’s what I did.

- Sold $3300 of McDonald’s to bring it back to 9% of the portfolio.

- With the $3300, bought shares in two other companies with better yields, one of which was new to the portfolio, and both of which had better valuations.

With this simple swap, I accomplished several goals.

- Reduced portfolio risk by trimming the oversize McDonald’s position.

- Improved the portfolio’s diversification and balance by adding a new position and bringing McDonald’s back into line with other positions.

- Increased the portfolio’s annual income stream by >1%.

- Kicked up the portfolio’s yield from 3.5% to 3.6%.

3. A position’s size increases beyond the maximum size that you allow in your portfolio

The example above illustrating overvaluation is also an example of keeping position sizes down where you want them. Doing so decreases “concentration risk,” which is the risk that a disaster with a single stock will have an outsized impact on your portfolio.

Many dividend growth investors do not tolerate position sizes as large as I do. I will let a position become 10% of my portfolio. From reading articles and comments around the Web, I have learned that many investors prefer to limit maximum position sizes to 5% or less of their portfolios.

Notice that as you reduce your maximum allowable position size, you must by simple math increase the number of stocks in your portfolio.

I consider the choice of maximum position size and number of stocks to be a personal decision. Obviously, the more stocks that you own, the less damage any one of them can cause if it blows up.

I consider the choice of maximum position size and number of stocks to be a personal decision. Obviously, the more stocks that you own, the less damage any one of them can cause if it blows up.

On the other hand, the more stocks that you own, the more there is to keep track of., and the less benefit you will get if one of them does really well.

A very common approach would be something like this:

- Maximum position size = 4% of the portfolio

- Target number of stocks = 25-30

Another approach that some investors use is to limit position size by the percentage of income that each position is responsible for, rather than by its market value. So, for example, an investor might say that no single position will be responsible for >10% of the portfolio’s income.

Both approaches are used in the Income Builder Portfolio that Mike Nadel manages for Daily Trade Alert.

4. The company’s dividend safety falls to an unsafe level

Many investors gauge dividend safety by looking at its payout ratio.

Payout Ratio Calculation

Based on earnings: Dividend per share / Earnings per share

Based on cash flow: Dividend per share / Cashflow per share

These numbers are easy to look up, and indeed some data providers display the payout ratios for you. Here is how they are portrayed for Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) at the Simply Safe Dividends website:

Payout ratios of <60% or <70% are usually considered to be safe, depending on industry.

Payout ratios of <60% or <70% are usually considered to be safe, depending on industry.

Unfortunately, payout ratios by themselves may be too simple to judge dividend safety. They may lead you to think that company’s dividend is safe when in fact it isn’t, and vice-versa.

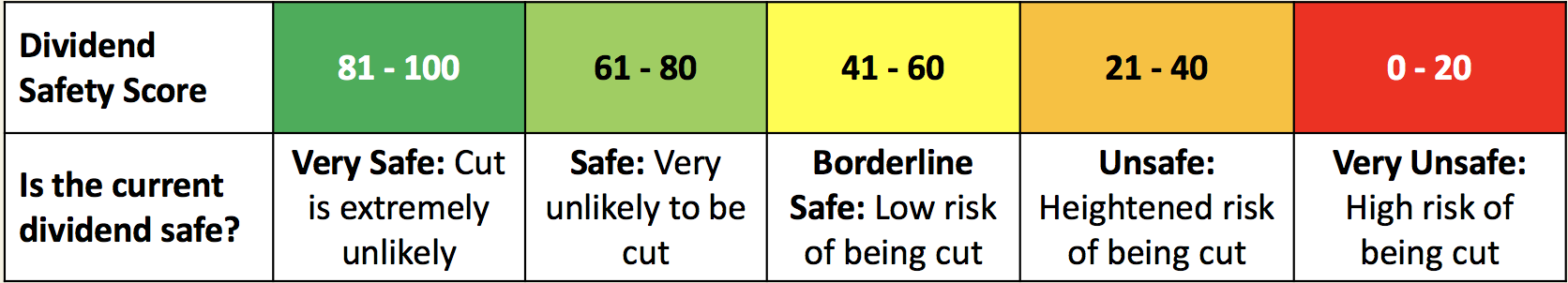

Therefore, I utilize the service that Simply Safe Dividends provides. They calculate a Dividend Safety Score for each stock based on a variety of factors, more than a dozen in all. These factors include:

- Payout ratios

- Debt levels and coverage metrics

- Recession performance

- Dividend longevity

- Industry cyclicality

- Free cash flow generation

- Recent sales and earnings growth

Scores range from 0 to 100:

In my own investing, I won’t consider buying a stock whose safety score is below 41, and indeed I usually buy stocks that are in the two green ranges.

In my own investing, I won’t consider buying a stock whose safety score is below 41, and indeed I usually buy stocks that are in the two green ranges.

If I already own a stock, I will consider selling it if its score drops below 41, especially if I have an ideal replacement on my watch list.

As you examine stocks, you will find that eye-catching high yielders often have wobbly dividend safety. Here is an example, GameStop (GME):

GameStop’s dividend yield is sky-high at >10%, but its dividend does not look sustainable upon an in-depth look.

GameStop’s dividend yield is sky-high at >10%, but its dividend does not look sustainable upon an in-depth look.

In contrast, stocks with more reasonable yields, in the 2.5% – 5% range, often have dividend safety scores that inspire more confidence. Here’s the well-known consumer giant Kimberly-Clark (KMB):

KMB’s yield is 3.6%, which may not sound all that exciting, but it’s very safe.

KMB’s yield is 3.6%, which may not sound all that exciting, but it’s very safe.

Other Reasons to Consider Selling

I have highlighted four reasons to consider selling above. You should also consider other reasons that make sense to you. Here are a few more suggestions:

- The company’s dividend growth rate (DGR) is in long-term decline.

- Its current yield rises above 9% percent or drops below 2%. The idea is that at 2% or less yield, the company is not paying me enough, or that at 9%+ something risky is going on that I ought to investigate. Sound reliable companies normally do not have yields over 9% in this day and age.

- Significant changes impact the company. Examples could be that it is going to be acquired; or it announces plans to split itself into two or more companies; or it announces plans to spin off a separate company.

Guidelines, Not Rules

When I first began as a dividend growth investor, I treated my selling guidelines as automatic rules. For example, if a company froze its dividend, I automatically sold it.

I have since decided that it’s better to consider these as guidelines rather than rules. The way I word them is, “Seriously consider selling or trimming if….”

The reason is that sometimes you may have a situation where the best decision, all things considered, is to hold.

For example, during weak economic times, a company may temporarily freeze its dividend. Many companies did that in 2008-09, and it was a prudent move. Then after the economic crisis and recession passed, they resumed their annual dividend increases. Obviously, such situations require case-by-case analysis.

Another example would be where a severe overvaluation does not take your position beyond your maximum size guideline. You may decide just to let the market do what it does (go up and down) and leave your holding alone as long as it is doing what you primarily want, which is increasing its dividend every year at an acceptable speed.

Even if a stock freezes its dividend, I want the flexibility not to sell it. Maybe the company has a good reason for the freeze, and it is clear that its dividend increases will resume shortly.

If you want to see how selling guidelines can form a part of an investment business plan, here are two examples:

Key Takeaways from this Lesson

- Deciding whether and when to sell are often more difficult decisions than deciding what and when to buy.

- Many investors shoot themselves in the foot by trading too much.

- Dividend growth investing can help guard against over-trading, because you are primarily watching your growing dividend cashflow rather than prices that hop all over the place. Cashflow is positive and usually growing, so it doesn’t create fear of market volatility.

- Dividend growth portfolios normally do not have a great deal of turnover. You are a collector of income-producing stocks rather than a trader.

- Nevertheless, there will be instances where the best thing to do to reach your long-range goals is to sell or trim a position rather than hold onto it.

- Articulate your selling guidelines in your business plan. Then you can consult your plan to remind yourself of how you analyzed these issues when you were calm rather than just reacting when a situation pops up.

- Realize that studying a situation and deciding to hold is an active step. That will help if you feel like you have to “do something” with your portfolio. That something is to investigate and reach a decision based on sound principles. It’s still an active decision even if it results in no changes to your portfolio.

Dave Van Knapp

Click here for Lesson 16: Diversification

This lesson was updated 10/18/2018