Yesterday, I shared the real secret behind Warren Buffett’s legendary track record…

In short, AQR Capital Management founder Clint Asness – in a thorough empirical study of Buffett’s track record – found that Buffett used leverage to magnify his gains on cheap, safe, high-quality stocks.

As I explained, this leverage was created by using the “float” from his insurance companies.

[ad#Google Adsense 336×280-IA]That’s the money that was paid in insurance premiums but not yet paid out in claims.

In today’s essay, I’m going to show you the key to finding companies that are safe enough to use leverage on, like Buffett has.

I’ll also show you how Buffett’s strategy drastically changed 15 years ago… and why this change has led to his lackluster results in recent years.

Let’s get right into it…

The key to finding companies that are good enough and safe enough to leverage is to look for highly capital-efficient businesses. These are simply companies that do not require much additional capital to grow. Please, if you haven’t yet, read my initial recommendation of Hershey. (We’ve “unlocked” the issue for you right here.)

I’m not a lucky “coin flipper.” And I’m not using Hershey as my example retrospectively. I told my readers at the time of my original recommendation that I believed Hershey would go on to be one of the best investments I’d ever recommended. And that’s what has happened, even though I recommended the stock just months before the worst bear market of our lifetimes. Even with the worst possible timing, this stock didn’t decline more than 25% from its highs… and it has produced excellent returns for our portfolio.

These are exactly the kinds of stocks that Buffett made a fortune buying, leveraging, and holding forever. And the thing that unites all of these stocks – financial stocks like Wells Fargo, branded consumer-products companies like Gillette, and insurance firms like GEICO – is their almost magical ability to grow sales, earnings, cash flows, and dividends without correspondingly large investments in their businesses.

In his research, Clint Asness’ team doesn’t spell it out this completely. But trust me, it is this particular quality – capital efficiency – that matters most. It’s what they really mean when they write “high-quality.” It is capital efficiency that allows companies to set high payout ratios (that is, they pay out a larger-than-normal percentage of earnings via dividends). The most common hallmark of capital-efficient companies is a noticeable lack of capital expenditures.

The most striking thing about Berkshire Hathaway today versus the years before 2000 is that its focus on capital-efficient businesses has almost completely disappeared.

Here’s an anecdotal example… In his annual letters to shareholders, Buffett has frequently explained his focus on capital-efficient stocks by pointing to the success of See’s Candy. He did so in this year’s letter (published a couple weeks ago)…

To date, See’s has earned $1.9 billion pre-tax, with its growth having required added investment of only $40 million. See’s has thus been able to distribute huge sums that have helped Berkshire buy other businesses that, in turn, have themselves produced large distributable profits. (Envision rabbits breeding.)

This is classic Buffett. This is his quintessential investment, much like Hershey is my quintessential recommendation. You never have to worry about companies like these going out of business. And you’re a fool if you ever sell them. They are virtual cash machines, creating profits while requiring almost no additional capital.

But consider how different this business is from the lion’s share of investments Buffett has made since 2000. His “powerhouse five” of wholly owned companies were all purchased after 2000: railroad firm Burlington Northern, regulated utility MidAmerican Energy, chemical giant Lubrizol, diversified industrial firm Marmon, and Israeli manufacturer Iscar.

These companies represented massive investments on behalf of Berkshire. Burlington Northern alone required a 6% dilution of the stock and $16 billion in cash (a total value of $44 billion). These are good businesses. They are not capital-efficient. Their need for additional capital to grow eats up most of their earnings. Berkshire earned $12.4 billion with this group of businesses this year. It will spend $15 billion on capital investments this year to grow, with most of this capital going back into the powerhouse five.

Buffett is going to spend $6 billion on the railroad alone this year. That’s more money than Berkshire made from all of its other wholly owned non-insurance businesses outside of the powerhouse five.

In summary, with the purchase of large heavy-industrial businesses, Buffett has transformed Berkshire from an insurance float-funded collection of the world’s highest-quality businesses into a global conglomerate of stable businesses with average economics.

The question for investors to ponder most carefully is if this new collection of businesses will weather the next major economic storm as well as Berkshire has in the past. My intuition? Absolutely not.

When you look at Berkshire’s cash flows and capital expenditures, this fundamental change in the business really jumps out. Berkshire had so few capital expenditures historically that prior to 2000, it didn’t even include capital expenditures as a line item on its statements. (You have to look in the footnotes to find the numbers, which are tiny.)

Prior to 2002, Berkshire spent less than 20% of its cash earned from operations on capital expenses. (Capital expenses are “lumpy” – with big charges in some years and almost none in others. To measure this, we use a five-year rolling average.)

But since 2002, these investments back into their own businesses have grown massively…

They now average 42% of cash earned from operations. This means that although Berkshire’s earnings may be growing (and fueling a matching rise in book value and stock price), the quality of these earnings has significantly declined. Most important, the growth in capital expenses means the business is producing far less free cash (as a percentage of profits). And that means there’s less cash for Buffett to invest. So Berkshire will almost surely see a big drop in the rate that it can compound its net worth.

Now… what does all this mean for investors?

First, it’s clear that Buffett isn’t doing nearly as good a job as he has historically with capital allocation. Berkshire’s book value isn’t compounding at nearly the rate it has historically. (It has underperformed the benchmark S&P 500 index in five of the last six years, and seems likely to do so again this year.)

Buffett explains this by making a circumspect argument (in my opinion) that his wholly owned portfolio of companies is not “marked-to-market,” so Berkshire’s book value doesn’t fully reflect the value of these companies’ increasing intrinsic value.

That is true. But it wasn’t meaningful until Buffett stopped being a great allocator of capital…

Think about See’s Candy. Sure, See’s is still valued on Berkshire’s balance sheet at its acquisition cost of $25 million. And yes, See’s is still worth a lot more than that. But Berkshire’s balance sheet has captured all of the $1.9 billion in retained earnings that See’s produced.

And because Berkshire hasn’t historically paid a dividend, this capital has produced tens of billions in book value for Berkshire via the earnings of other companies and the shares of other companies Buffett purchased with this capital.

You don’t need to follow all of the accounting. Just remember this… Buffett is a smart man. He chose what his benchmark would be – increasing book value by more than the S&P 500. For decades, he said that if he couldn’t do this, he isn’t doing his job and that Berkshire should either replace him or begin paying dividends.

After never losing to the S&P in any five-year period before, Buffett has now lost for essentially six years in a row. That explains far more about him deciding to change his benchmark than the accounting complexities. So… investors should be careful about extrapolating into the future the returns that Berkshire has made in the past. Doing so will almost surely cause significant disappointments.

Here’s another interesting way to see what’s happening with Berkshire…

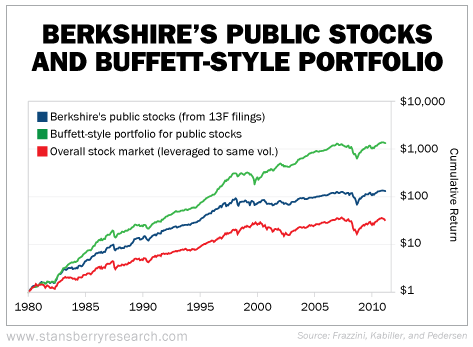

This chart shows the Asness group’s “Buffett index” – the large number of stocks that match Buffett’s historic investment criteria (cheap, high-margin, and capital-efficient). This index (in the green) represents the performance of the kind of stocks Buffett has historically invested in. That’s why the blue line – the actual performance of Buffett’s portfolio – tracks it so closely.

The Buffett index is going to show some outperformance over time because it is only a paper portfolio. It doesn’t pay taxes or transaction costs. Also, the index is going to do a little better because it is far more diversified than Buffett’s actual portfolio. Even so, those factors don’t explain why the relative outperformance of the Buffett index has increased so much since the late 1990s.

There can be no doubt that the Buffett of the last 15 years isn’t doing nearly as good a job as he once did. He has had dozens (or even hundreds) of opportunities to buy incredibly high-quality businesses at dirt-cheap prices over the last 15 years. My newsletters have recommended plenty of them: Tiffany, Starbucks, Hershey, Harley-Davidson, eBay, Disney, and McDonald’s, to name just a few.

But Buffett didn’t buy any of these great businesses. Instead, he spent $44 billion on a railroad. That’s 44 times more capital than he invested in Coca-Cola. He also invested $15 billion in IBM, which he specified by name in his 1996 letter as one he would never buy. Few investors realize how critical these decisions will become over time.

And that’s the bigger question: Will a portfolio dominated by slow-growing, highly regulated and competitive businesses with large, ongoing demands for capital investment be able to withstand an economic storm? Maybe. But it’s no longer the sure thing it used to be.

Regards,

Porter Stansberry

[ad#stansberry-ps]

Source: Daily Wealth